| Unit or location | Role | Posted from | until |

|---|---|---|---|

| Battle Patrols | Scout Section Member | Unknown | Unknown |

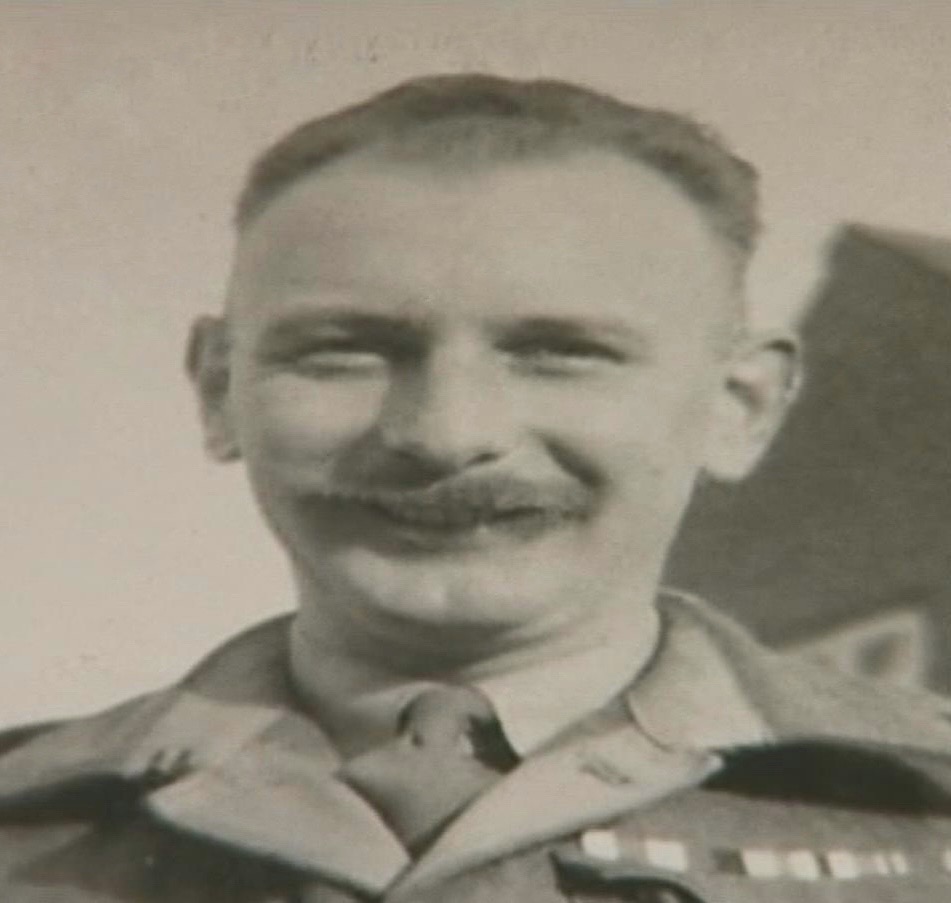

Major Henry Hall, MC, 4th Battalion, The Dorset Regiment. Henry Hall first came to Kent in September 1939 when he was stationed at the Daily Sketch children's holiday camp at St. Mary's Bay and at Shorncliffe Barracks, Folkestone, as a member of the Artists' Rifles Territorial Battalion. Soon after he was commissioned and sent to Weymouth to join the 4th Battalion, The Dorset Regiment, as part of the 43rd Wessex Division.

On 8th September 1940 the codeword 'Cromwell' was broadcast which meant — Invasion imminent. Church bells fell silent, not to be rung again until the invasion actually happened. The 43rd Division moved to Hatfield Forest, north of London, to form part of the GHQ Reserve, which meant that had the Germans landed in Kent, which was defended by XII Corps, they would counter attack London if the Germans had got that far. He remained in Hatfield Forest until the end of September 1940 when stand down from Invasion was announced. He then moved back down to Kent and came under the command of XII Corps. He was first stationed in the Dover area and defended the beach at St Margaret's Bay. After that he was moved to various places in Kent and at the end of 1940 was stationed in the Cavalry barracks at Canterbury.

In 2005 Major Hall recalled what happened next and how he became, in 1941, the much- admired and remembered thuggery instructor for the civilians of the XII Corps Observation Unit:-

"General Andrew 'Bulgy' Thorne formed Battle Patrols in each Battalion, with the same job as the Resistance Organisation, which was to stay behind after the enemy had invaded and then pop up and cause havoc amongst the enemy once they had landed. Exactly the same job the SAS had in the Cold War. One day I was ordered to go and see our Commanding Officer and when I arrived in his office I found a Sergeant, John Davidson, there as well, whom I had never seen before. We were told that he had selected us to go on an 'Advanced Assault Course' in Scotland.

In early 1941 we went to Inverailort in the Western Highlands of Scotland. We went up there by train from Canterbury all the way to Fort William and then we got on the little puffer train that used to go from Fort William to Mallaig, now called 'The Jacobite.' We were sitting there comfortably in the train when all of a sudden the train came to an abrupt halt. We were all thrown forwards, our kitbags came off the luggage racks and the place was a shambles. Then we realised the train was under fire and that explosions were going off all around us. Then instructors leapt out of holes in the ground and shouted: 'Get out of the train! Get out of the train! Grab your kit and follow us'! So of course we all scrambled out, grabbing everything we had and we were doubled, ran all the way to the Big House clutching our belongings. We were shot at all the way as we were running the mile and half to the Big House and when we arrived there we were shown some Nissen huts on the lawn and told: 'Find yourselves a bed, that's where you're going to live'.

All modern close-quarter and guerrilla methods and tactics stem from the teaching given at the Big House. It was formed into the Irregular Warfare Training Centre in June 1940 in order to train guerrilla leaders. The Independent Companies were formed there and SOE started its life there under Colin Gubbins, before it changed its Headquarters to Arisaig House. The Commandos started life there before they were transferred to the Training School at Achnacarry under Charles Vaughan.

Independent Companies were formed by Lord Lovat for raiding purposes and, when he decided to mass produce them, they were called Commandos, in honour of his grandfather who commanded The Lovat Scouts who had fought so successfully in the Boer War against the Boer Kommandos. It was Bill Stirling's idea to start the Irregular Warfare Training Centre to train guerrilla leaders. Lord Lovat requisitioned the whole area from Fort William to Mallaig. Gubbins got on to General Ironside, the GOC Home Forces and the formation of the Irregular Warfare Training Centre was authorised in June 1940.

The first courses were about 30 strong of Officers and Sergeants. They lasted three weeks and anybody who didn't come up to scratch was returned to unit immediately. David Stirling, who formed the SAS, and Fitzroy MacLean, who joined David in the SAS and then went to Yugoslavia to help Tito settle the Balkan problem, both attended the first course. Fitzroy attended it in plain clothes (because he was not yet in the Army, he was still in the Foreign Office). The Commanding Officer was Bryan Mayfield of the Scots Guards, the Chief Instructor was Bill Stirling of the Scots Guards, the Assistant Chief Instructor was Freddie Spencer Chapman of the Seaforths, a Polar Explorer who eventually spent two years alone in Malaya helping the Chinese to fight the Japanese. Fieldcraft was taught by 'Shimi' Lovat of the Scots Guards and Lovat Scouts. He ended up commanding the Commando Brigade. The Assistant Fieldcraft instructor was Peter Kemp and later David Stirling of the Scots Guards. Bill and David were cousins of 'Shimi' Lovat. Demolitions were carried out by the famous Mike Calvert, Royal Engineers, who made a real name for himself in the Chindit campaign. Jim Gavin assisted him, he was an Everest climber. Later on others joined as instructors — Martin Lindsay from the Gordons who was a Polar Explorer, Peter Fleming, who with Mike Calvert, helped to form the Auxiliary Units, Gavin Maxwell and Captain Scott, a Polar explorer and descendant of the famous Captain Scott.

There is an organisation called MI(R) — Military Intelligence (Research). Even now they are thinking of ideas to deal with contingency plans, looking for people with special skills and abilities and devising various instruments for surveillance, demolition and everything else you can think of. Two key figures at Inverailort were 'Dan' Fairbairn and 'Bill' Sykes. MI(R) discovered them in the Shanghai Police Force. Their speciality was close quarter combat, silent killing and dirty tricks. 'Dan' Fairbairn was the first European to be awarded a Black Belt.

On the first morning after our arrival we met 'Dan' Fairbairn and 'Bill' Sykes. We were taken into the hall of the Big House and suddenly at the top of the stairs appeared a couple of dear old gentlemen (we later discovered one was 56 and the other 58). Both were wearing spectacles and both were dressed in battle dress with just a plain webbing belt. They walked to the top of the stairs and fell, tumbling, tumbling down the stairs and ended up at the bottom in the battle crouch position with a handgun in one hand and a fighting knife in the other. A shattering experience for all of us. Fairbairn was the elder of the two. He was about 5 feet 10, lean faced and lean bodied, a tough leathery looking man, a taciturn character, he never spoke very much, except to say: 'Stick a knife in here', or 'Hit him here', or 'Put your thumb in his eye', or whatever. He kept himself to himself and I think he considered himself to be a little better than Sykes.

Sykes was a much more gregarious character, slightly shorter than Fairbairn, average build, certainly not on the lean side, he looked more like a bishop than anything else. He was easy to talk to, a pleasant character. One day I asked him about sharpening my fighting knife, he said: 'Come up to my room, I'll hone it for you'. Which he did. Two completely different characters, they hated each others' guts but they worked together as a wonderful team and they both taught exactly the same things. Their speciality was close-combat fighting and silent killing. They had learnt their trade on the waterfront of International Shanghai. They had absolutely no respect for the Geneva Convention. They said: 'If you think our methods are not cricket, remember that Hitler does not play this game'.

First of all they taught us how to fall — a continuation of their falling down the stairs, they taught handgun and knife work and neck breaking. Now, when you are attacking somebody the clothing that they are wearing and their equipment must be considered. For example, if a fellow is wearing a greatcoat you can't kick him in the parts because the blow won't have any effect. You have got to hit him somewhere else. If you suspect that someone is wearing body armour you can't stick a knife into his chest, although the favourite place for sticking knives in, taught by Fairbairn and Sykes, does work even with body armour. We were taught releases. If you are grabbed by somebody from the back, front, side or whatever, how to get out of his grip. We were taught 'come-along grips' — how to take a prisoner along safely without him being able to escape. We were taught the use of sticks, anything from four inches to six feet long; a four inch stick is just held in the hand and you can strike with the end of the stick and give a chap a nasty knock with it. A stick can be anything, an actual stick, a rifle, something you pick up in a farmyard. A clipboard for example is a stick, you can strike somebody with it across the side of the neck, on the head, on the nose, under the nose, you can hit him in the parts, you can hit him in the solar plexus, almost anything is a stick. A stick is always held in two hands as exemplified by Robin Hood and Little John. They taught the use of coshes, they preferred the spring type best, longbows, crossbows, catapults, garrotting, with anything that happens to be handy — a scarf, string, wire, anything you like; the use of shovels — every good soldier always carries either a pick or a shovel and you simply use it to chop off a chap's head, or whack him on the shoulder, or just use it like a battle axe. You can do the same with a tin hat, just whip the tin hat off and use the side of it to hit him in the face or whatever part happens to be handy. We were taught mouth slitting, ear clapping, ear tearing and eye gouging. Also, rib-lifting, nose chopping, shin scraping, shoulder jerking, the bronco kick, and the bone crusher.

Fairbairn and Sykes also taught the use of the hand gun. They favoured the 9mm Browning. Now, if you hit a man with a 9mm bullet it will not stop him. If you use a .45 or anything larger, such as a shotgun, that will stop him dead, maybe blow him backwards. With a 9mm round you need two shots to stop a man dead and so Fairbairn and Sykes taught the Fairbairn Sykes 'double tap'. You draw your handgun, two shots, 'pom pom', and the chap is dead. They carried their handguns in the right hand trouser pocket. The normal opening of the trouser pocket is a little bit higher than where your hand naturally hangs and so they modified the trouser pocket so that you hand could go into the pocket with your arm at its normal length. The holster of the handgun was sewn into the inside of the pocket. The inside of the pocket was sewn to the trouser so that when you drew the handgun it came out without snagging on the pocket. They carried the fighting knife in exactly the same way, in the left hand trouser pocket. I carried my handgun and fighting knife that way during the whole of the War. One thing they did emphasise, particularly with the handgun, was to count the number of shots you had fired so that you were never caught with an empty magazine and therefore unable to get a round off at your enemy.

Now the Fairbairn Sykes knife. Fairbairn and Sykes developed the knife in Shanghai, incidentally they never mentioned Shanghai at all at Inverailort, I didn't discover they had come from Shanghai until years afterwards. When they got back to England they went into Wilkinson's in Pall Mall and got hold of one of the Directors and explained exactly what they wanted and what they wanted was a seven and a half inch blade made from one piece of metal right from the tip of the haft right down to the point and then with the guard put on and then the handle, the grip. The grip was to be checkered so that you could hold it whether it was wet or bloody. Each was individually handmade, sharpened and honed so that your knife should be able to cut a piece of paper. I bought mine, one of the original Number 1 knives, in Pall Mall for thirteen shillings and sixpence. Later on they developed various other models for economy purposes. The Fairbairn Sykes knife is straight. If you are using it for slashing cuts you use it like a paintbrush, stroking it so that when the blade hits the surface you are trying to cut, it cuts at an angle, on the principal of the curve of the samurai sword. You held the knife between the thumb and forefinger just behind the guard. The knife was perfectly balanced and so you could throw it from hand to hand. As you carried it in your left hand pocket, if you were right handed you could draw it with your left hand, throw it to your right hand and catch it quite easily, no problem at all. The guard was not to stop the other chap's knife from cutting your hand but to stop your hand going down and being cut on the blade when you made a thrusting blow. They taught many other blows, vulnerable points and so on, but the snag is that with a man with equipment on or doing it in the dark you just don't know what equipment he has got on and you can't find a vulnerable point or somewhere to stick the knife.

I think the great advantage of the advanced assault course at Inverailort was that it gave you so much confidence. You knew so many more tricks of the trade and methods of attack, demolition and causing havoc and destruction that you became super confident. Whatever you did, you did it automatically, subconsciously. The answer to whatever attack you were up against would be an instinctive reaction."

When Henry Hall and John Davidson returned to Canterbury, Hall was given command of a Battalion Battle Patrol. The Commanding Officer, Harold Matthews, had selected three experienced Corporals and thirty men for the Patrol. Hall's first task was to train and teach them all he had learnt at Inverailort.

Hall recalled: "We had each been issued with a bicycle and a mass produced blackened Fairbairn Sykes Fighting Knife. Sergeant Davidson and I had been issued with an escape compass. My blackened knife and compass are in the British Resistance Organisation Museum in Suffolk. My No 1 knife was taken by the RAMC when I was wounded! We also had gun cotton, 808, primers, detonators, safety fuse, cortex, time pencils and all types of switches. We were administered as an ordinary infantry platoon and part of a rifle company, but I was in command, not the Company Commander.

Our first task was to get to know Kent by heart. We went off for days on end exploring every nook and cranny, living off the land. I was then given our operational tasks which were:-

A secret one. To go to ground if the enemy invaded and then, on my own initiative, cause as much havoc against troops and communications and dumps as possible, our true role. We never had any holes in the ground like the Auxiliary Units had; simply because at that time I'd never heard of them because they were so secret.

Our second task. To act as the enemy on Battalion or Brigade exercises, to test the security of HQ and dumps and to test the vulnerability of communications in the Brigade area.

A propaganda role. We practised on a mock Landing Craft on the beach near Deal for a raid on Dieppe and were encouraged to talk about our 'raid' in pubs and public places.

We had a wonderful time swanning about Kent doing just what I wanted us to do, improving our training and perfecting our techniques for these tasks. We gave demonstrations of our skills to Battalions in our Brigade and to various training schools. Then one day I was ordered to do an exercise umpired by our Brigade. We landed at dusk on a remote beach near Herne Bay and had to rendezvous with an 'agent' at a map reference (in an allotment hut near Ashford) with a Battalion in our way to stop us. We were given orders by the 'agent' to attack a farm below Charing Hill at dawn, lay up during the day and get back the next night, again through a Battalion, back to the beach where we had landed. All went well. After a few days I was told by Harold Matthews that I had won the Brigade Battle Patrol competition. Up to that time I had no idea there were any others anywhere. I still don't know how many others there were, I never met nor had anything to do with any nor heard of any. But each Battalion must have had one.

I carried on learning more about Kent, giving demonstrations, testing security etc and one day I was told to meet an officer at a map reference (Norman Field, I learnt just a few years ago) who told me he commanded the XII Corps Observation Unit and we were to lay on a demonstration for 130 Brigade, which we did near a gravel pit (which I used for grenade work) near Canterbury. He then asked me to help him train his men in dirty tricks, I would meet unknown men at map references at night for several months.

So things went on very happily for me and we achieved a high standard of efficiency. I had introduced the use of a bird call which I used in Kent instead of a whistle and in action to identify ourselves when returning through our own lines, also a Totem — a six foot holly pole with a brass jug which we had pinched from a pub in Sandwich and my whole patrol had scratched their names on it. On top of the pole was the skull of a cow!

In August 1943 I left Kent and moved to Bexhill where training increased for what we later found out was going to be D Day. I reverted to a normal Infantry Company Platoon. Sergeant Davidson disappeared. As far as I know he was taken into the SAS as were many members of the Resistance Organisation to form the 'Jedburgh' groups."

I thank God I was trained so well at Inverailort and knew all the tricks of the trade, dirty and otherwise and had such confidence in myself and in my men that I was able to survive for six months during the war, do considerable damage to the enemy and brighten up the battlefield now and again with a laugh and a joke and a few silly things.

In 2004, with the help of his daughter, Henry talked to the BBC of his wartime roles.